2. Types of Adrenal Insufficiency

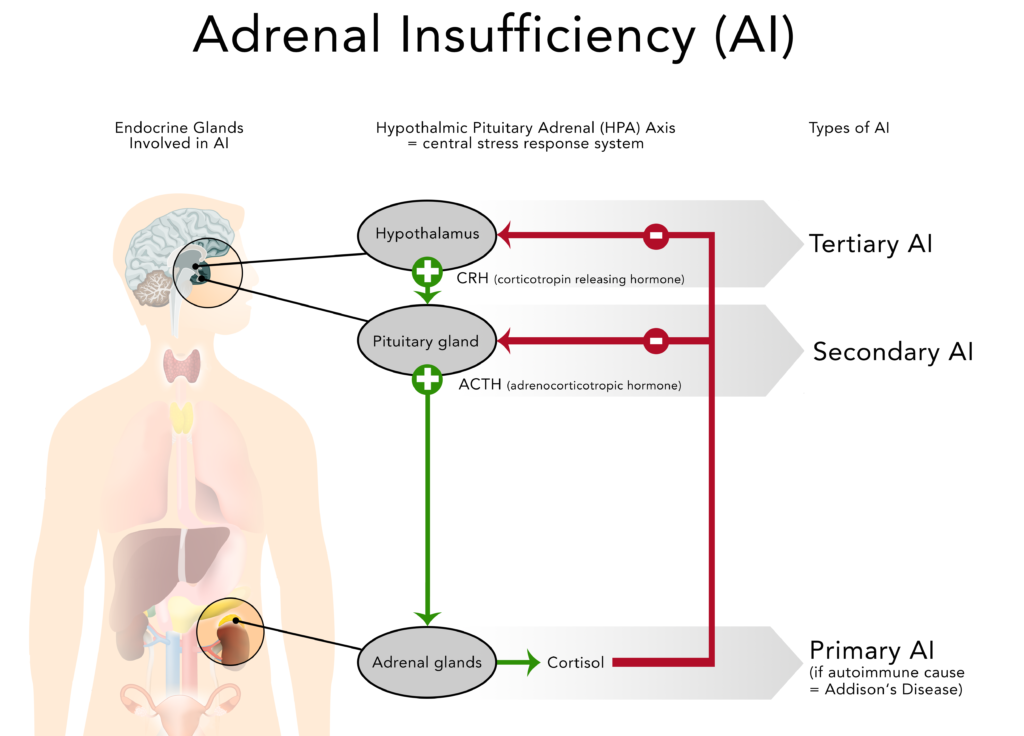

The failure to produce sufficient levels of cortisol can occur for different reasons. Depending on the underlying mechanism, the problem may be due to a disorder of the adrenal glands themselves (primary adrenal insufficiency or PAI), inadequate secretion of ACTH by the pituitary gland (secondary adrenal insufficiency or SAI) or impaired production or action of CRH from the hypothalamus (tertiary adrenal insufficiency or TAI).

2.1. Primary Adrenal Insufficiency (PAI)

Primary adrenal insufficiency develops in about 4 of 100,000 persons annually (= incidence), and studies report between 82-144 cases per one million of the population (= prevalence). It occurs in all age groups and about equally in each sex.

GOOD TO KNOWThe difference between incidence and prevalence

Incidence and prevalence are commonly used terms in describing epidemiology of diseases. Incidence is the rate of new (or newly diagnosed) cases of the disease within a period of time (e.g. per month or year). Prevalence is the actual number of cases during a period or at a particular date in time.

Approx. 80% of cases of primary adrenal insufficiency in developed countries are caused by autoimmune adrenalitis, also called Addison’s disease. An autoimmune disease occurs when a person’s immune system produces antibodies that attack the body’s own tissues or organs and slowly destroys them. In the case of Addison’s, this leads to the gradual destruction of the adrenal cortex (the outer layer of the adrenal glands. Symptoms of adrenal insufficiency occur when at least 90% of the adrenal cortex has been destroyed. As a result, often both glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid hormones are lacking.

Tuberculosis (TB) accounts for about 10-15% of cases of primary adrenal insufficiency in developed countries (the percentage in developing countries or among immigrant populations is much higher). When adrenal insufficiency was first described by Dr. Thomas Addison in 1849 tuberculosis was found at autopsies in 70% to 90% of cases. As treatment options improved, the incidence of adrenal insufficiency due to this infectious disease greatly decreased.

Further causes of primary adrenal insufficiency are other chronic infections such as AIDS, syphilis or fungal infections, tumours/metastases, acute haemorrhage in both adrenal glands, amyloidosis or the removal of both adrenal glands due to other conditions.

It is important to note that the percentage of the various causes of primary adrenal insufficiency in children differs substantially from that in the adult population. In children, the genetic forms are more common: congenital adrenal hyperplasia accounts for approx. 70% of adrenal insufficiency, other genetic disorders for approx. 6% and autoimmune disease for only 10-15%.

2.2. Secondary Adrenal Insufficiency (SAI)

Secondary adrenal insufficiency occurs more frequently than primary adrenal insufficiency, with a prevalence of 150–280 per one million of the population.

Secondary adrenal insufficiency can be traced to a lack of ACTH which is produced in the pituitary gland and causes a drop in the adrenal glands’ production of cortisol (but not aldosterone). Any condition that affects the pituitary gland or its production of ACTH can therefore result in secondary adrenal insufficiency:

- removal of parts of the pituitary gland due to a benign (non-cancerous) ACTH-producing tumour. In this case, the source of ACTH production is suddenly removed and replacement cortisone must be taken.

- shrinking of the pituitary gland or decreased production of ACTH due to tumours or infections of the area, loss of blood flow to the pituitary or radiation for the treatment of pituitary tumours.

- removal of the pituitary gland during neurosurgical procedures with the goal to treat other conditions.

- traumatic brain injury.

Suppression of HPA Axis due to Steroid Therapy

The most common cause of an induced adrenal insufficiency is the long-term use of steroids to treat other chronic conditions such as asthma, rheumatoid arthritis or ulcerative colitis. The high doses of prescribed steroids (such as prednisone or dexamethasone) suppress CRH and ACTH production in the otherwise healthy hypothalamus and pituitary gland which in turn leads to a suppression of the body’s own cortisol production (see also: HPA, negative feedback loop) in the adrenal glands.

DON’T FORGET!If a person who has been taking long-term steroids abruptly stops or interrupts taking the prescribed steroids and their adrenals have stopped producing sufficient levels of cortisol, they can go into adrenal crisis.

A slow and gradual reduction in steroid dosage under medical supervision is needed to give the adrenal glands time to resume normal functioning (weaning / tapering).

The amount of time it takes to taper off the steroid medication depends on the condition being treated, the dose and duration of use and other medical considerations. It is important to know that the suppression of cortisol production cannot always be reversed, therefore leading to permanent secondary adrenal insufficiency.

See also: Glucocorticoid tapering and testing guide

2.3. Tertiary Adrenal Insufficiency (TAI)

Tertiary adrenal insufficiency results from the impaired production or action of CRH from the hypothalamus which in turn inhibits the secretion of ACTH from the pituitary gland. As mentioned above, tertiary adrenal insufficiency can also be caused by long-term steroid therapy.

GOOD TO KNOWBecause the hypothalamus and pituitary gland are part of our brain (also called central nervous system) secondary and tertiary adrenal insufficiency are sometimes referred to as “central adrenal insufficiency” or “central hypoadrenalism”.

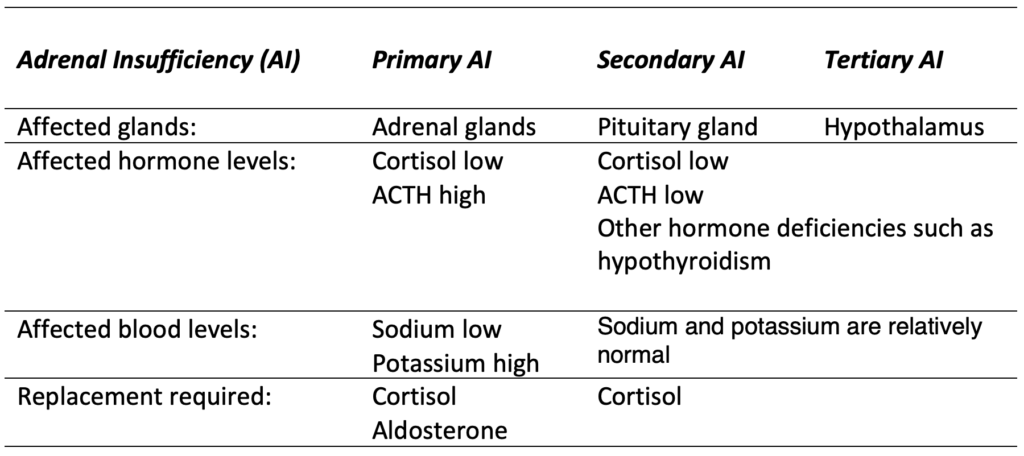

2.4. Comparison of primary, secondary and tertiary AI

> NEXT CHAPTER

> CHAPTER OVERVIEW

Anatomy/Physiology | Types of Adrenal Insufficiency | Symptoms | Testing/Diagnosis | Treatment | Stress dosing/Sick day Management | Adrenal Crisis | Quality of Life and Risks | Other Conditions and Drugs | Long-term Management | Suggested Reading | Literature/References

Author: Gisela Spallek, MD PhD; graphics by spallek.com

Edited by Maria Stewart, Director of AIC and deputy editor Des Rolph, Associate Director of AIC